Afrobeats To The World: Nigerian History Is Repeating Itself

Everything happening to Nigerian music today has happened before. Our fathers got it wrong, but we don't have to.

Everything happening to Nigerian music today has happened before. This aspirational flight of our music from local studios to international audiences via global music corporations and their local operators is in its second coming. ‘Afrobeats to the world, as love to call it, isn’t new. It’s history repeating itself — a collective deja vu for our creative class and the ecosystem that supports it.

We have seen this before. Our ancestors — your parents and their parents — have been here before. The influx of new cash from global music corporations. The growth of the industry stimulated by value generated from overseas capital. The boots on the ground, emerging from connecting flights with big dreams about cornering market share in Lagos. The cross-cultural mixers overflow with the elite of the music industry. Fluid cultural exchange crystallised as cross-market artistic and brand collaborations. The tours, concerts and performance circuits that graciously open their arms to our ‘new’ sounds. Today is yesterday, only garnished by Tiktok and our global pop acceptance.

Nigerian sounds have always pushed beyond Lagos. The history books, where we can find them, reveal this. But to this new generation of creatives, industry operators, and consumers who lack an awareness of the past, we are in unfamiliar territory. One that has promised and delivered giddy highs, imbued a global sense of pride in our diaspora communities, sprayed cash advances and their attendant contracts around the city, and altered the landscape of the music business in Nigeria. We currently have a creative class, deeply ensconced in foreign markets via a plethora of deals that formalise these partnerships.

And while the mood in Lagos is a cross between novel wonder and hyperactivity, it reminds me of our past when we experienced similar from the 1970s to the early 1990s.

From the late 70s, through the 80s Nigerian music experienced a cultural explosion. Same as we’ve had from the late 2000s to this point, using the same formula of creativity. Music hopefuls and would-be stars embraced and redefined foreign pop and traditional sounds from the US, UK and our neighbouring countries, creating a fine blend with our local sounds and peculiar interpretation of music. The end of the civil war firmly in our past, the creative scene from Lagos to Enugu and Port Harcourt flooded with legendary musicians who mined their reality across the nation to create hits. From the mid-70s, music movements sprouted all around the country, with Highlife (drawn from Ghana), Funk, Rock, Psychedelia, Disco, and many others played in live venues by locals who had found a local spin to accommodate global trends.

With Nigeria being the most populous country in Africa and Lagos being a truly international city, many dancefloor-orientated genres – Afrobeat, Afro funk and Afro disco—flourished there in the 1970s and 80s. Despite its bloody colonial history and terrible dictatorships after 1970, there was still rich cultural exchange between Nigeria, the UK and US. A huge live-first market, bands made a killing by playing across clubs, venues and concerts all around the country. These were the glory days of Nigerian classical music giving us a retinue of stars including Orlando Julius (Afro-disco), Fela Kuti (Jazz and Highlife, later Afrobeats), Segun Bucknor (soul, pop, funk), Chief Stephen Osita Osadebe (Highlife), Oliver De Coque (Highlife) and more.

The 80s also brought us an explosion of Reggae, a genre from Jamaica, minting local stars such as Ras Kimono, Evi Edna-Ogholi, Majek Fashek, and many others. Check the books, Nigeria has a long history of producing stars with a focus on reimagining foreign music concepts to create local hits.

And the foreign companies came in to do business. Yes, they all did.

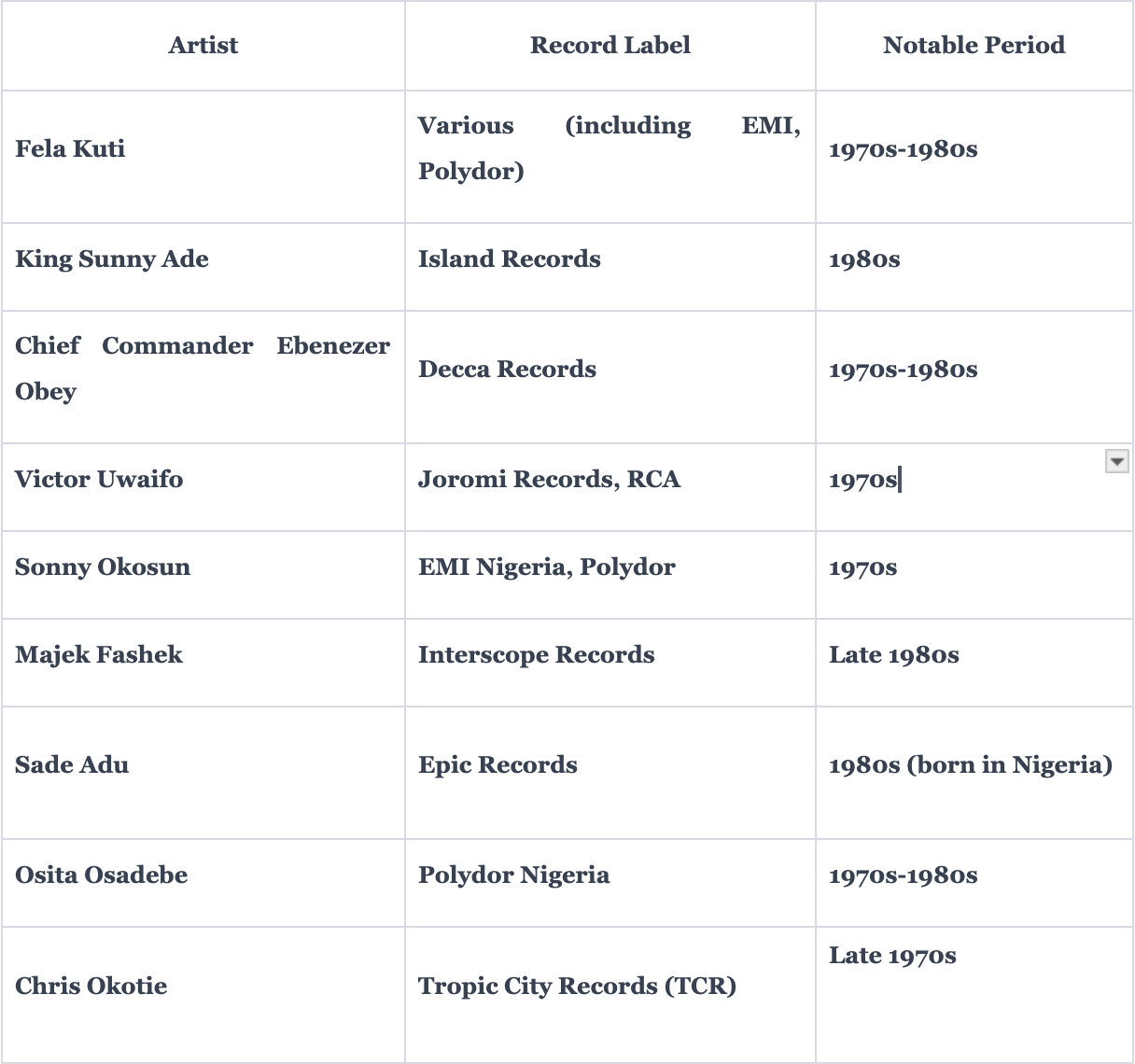

Look through the discography of all our music heroes past, and one common denominator in how many conducted their music business was their dealings with global music companies and their subsidiaries.

Take King Sunny Ade, for example. The ‘Wizkid’ of his time, attained pop success at levels that draw parallels to today. Sunny Adé introduced the pedal steel guitar to Nigerian pop music. He also introduced the use of synthesizers, clarinet, vibraphone, and tenor guitar into the jùjú music repertoire such as dub and wah-wah guitar licks. After Bob Marley died in 1981, Island Records (Universal) signed KSA to their books to fill those shoes.

Famed French producer and journalist, Martin Meissonnier, introduced King Sunny Adé to Chris Blackwell (Island Records founder), leading to the release of his major label debut album, Juju Music in 1982. Billed as “the African Bob Marley,” he gained a wide following with this album. Two Grammy nominations in, he left the label because he refused to allow Island to meddle with his compositions and over-Europeanise and Americanise his music. He didn’t want artistic tinkering for a larger audience, and Island looked elsewhere.

Fela Kuti signed to Arista (Sony), Polygram (Universal), EMI (Universal), MCA/Universal and more during his storied creative run that moved from Jazz and Highlife to Afrobeats. Prince Nico Mbarga was born in Abeokuta, and is famed for his ‘Sweet Mother’ classic. His first record deal came via EMI, but he was dropped because of his band’s inability to crossover. ‘Sweet Mother’ would later invalidate that analysis, after it sold 13 million copies worldwide.

Segun Bucknor, made soul, pop, funk and a version of Afrobeat. During his brief career he was released records under, Afrodisia the local label launched in 1976 by Decca West Africa in Nigeria. The label released several albums by Fela Kuti, as well as several other artists and bands, e.g. the Oriental Brothers International Band. How about Majek Fashek and his Interscope Deal?

Today’s Nigerian creative landscape offers up some parallels. Afrobeats as a movement still obey the same principles that gave us our legendary classical age. While Nigerian creatives of the past utilised elements from Disco, Funk, Rock & Roll and Soul to make local fusions, today’s creative class have ushered in an era inclusive of hip-hop, R&B, Dancehall, and more. Our forbears borrowed and indigenised Highlife from our neighbours in Ghana. This generation takes everything else, including Azonto, House, Gqom, Amapiano, and more from neighbouring cultures.

Afrobeats to the World has put Nigerian stars on all the major global award shows including the Grammys. King Sunny Ade also has a 1984 Grammy Award nomination. He received a nomination in the Best Ethnic or Traditional Folk Recording category for his album titled "Syncro System." Fela Kuti, the Afrobeat pioneer, received a Grammy nomination in 1981 for his album "Olatunji Concert: The Last Live Recording" in the Best Ethnic or Traditional Folk Recording category.

Burna Boy has Coachella in his rearview mirror, while Wizkid headlined Glastonbury in 2023. In the same way, Fela Kuti has also headlined Glastonbury, and performed at the Berlin Jazz Festival. Burna Boy has played on the Jimmy Kimmel Live! show, using the same conveyor belt that took Majek Fashek to the David Letterman show.

Why The Majors Left & Lessons For Today

The record labels left for all the right reasons after they struggled to generate and sustain value.

Economic challenges were a factor. Nigeria faced economic downturns in the 1980s, including a decline in oil prices, which had a significant impact on the country's overall economic stability.

The country also experienced periods of political instability and military rule during the 80s and early 90s. And rampant piracy struck the final blow. During this time, the unauthorized reproduction and distribution of music resulted in substantial financial losses for both local and international record labels. The lack of effective copyright protection and enforcement made it challenging for labels to sustain profitable operations.

We had a poor, unstable country, riddled with piracy and a lack of global attention.

It also didn’t help that Nigerian music did not maintain a permanent place in world music. The global music industry underwent significant changes in the 80s and 90s, with the rise of new genres and formats. The focus shifted to other regions and markets where there was a perceived potential for greater financial returns. As a result, some international labels redirected their efforts to emerging markets or genres that were gaining popularity elsewhere. The shift in distribution models, with the rise of digital technologies and changes in consumer preferences, also played a role. The traditional record label model faced challenges globally, and some labels may have restructured or withdrawn from certain markets as a part of broader strategic adjustments.

Nigerian record labels and artists were also becoming more established and competitive during this period. Local labels gained prominence, and some artists preferred working with Nigerian companies, reducing the reliance on international partnerships. Examples include Joromi Records, Premier Music, Tabansi Records, Rogers All Stars, Sunny Alade Records, and Ivory Music.

Lessons From History Repeating Itself

Three decades after its capitulation in the 90s, the Nigerian music industry is having a renaissance, back in its glory days as the toast of world music. And this time, the companies are back again. They’re here to mine and export culture, just like they tried and failed to in the past. We have offices of global music corporations sprawled all around Lagos, with partnerships with local operatives expanding their corporate wingspan.

What do they have going for them? Afrobeats has finally cracked the global pop framework. Nigerian artists like Wizkid, Burna Boy, Ayra Starr, Rema, Omah Lay, and many others have connected to new audiences beyond Africa, discovering and consolidating new homes abroad, backed by a vibrant diaspora across the US and Europe. Backed by contracts signed in swanky offices around the world, they have access to financial war chests, with their music serviced to consumers via the world’s greatest distribution and marketing pipeline.

The older generation made inroads into niche communities and were celebrated for their artistry. But they were sorely absent in the dance and pop circuit of the 90s and 80s. Fela Kuti didn’t share a playlist with Madonna or Michael Jackson. Elton John and King Sunny Ade didn’t marry their communities to find common ground. But Burna Boy and Ed Sheeran are contemporaries on the front-end and respected in equal degree in the business.

Afrobeats to the world is reliant on external love. That’s the only way to make sense of the economics of foreign investment.

But old pitfalls still exist. All the fatal problems from the late 80s an 90s still plague Nigeria. The local market cannot sustain itself. The infrastructure to generate value from the 200 million-strong population is non-existent. Nigeria lacks a standard live music venue and a touring circuit. Nigerians access the bulk of their music via piracy, with limited enforcement of the copyright act keeping Apple Music and Spotify numbers comparatively low.

As an economy, Nigeria is currently experiencing record levels of inflation. While music is a basic need, the music industry is struggling to convert local utility into financial profits.

Just as it was in 80s and 90s. So it is today.

Afrobeats to the world is hanging by a thread. Without the local numbers to back our claim, we are at risk of being exposed and abandoned when pop music inevitably shifts its focus to another emerging sound. It's another shiny thing. Look towards global music interaction with dancehall and the Caribbean creative class of the early 2000s for a lesson on capital flight, and how that can crush an entire industry.

History always repeats itself, and there’s the opportunity to utilise this new boom to chart a new course, different from our fathers. One that solves our most glaring problems, ensuring we eat today. And also tomorrow.

Good article Joey, of course its good to sound the alarm bells backed by research but it would also be nice to outline practical steps afrobeats people need to take in order to avoid repeating the mistakes of the past.

Insightful piece 💯

History is bound to keep repeating itself if we keep dancing to her tune blindly.

Can we fight it? If we do, can we win it?🤔